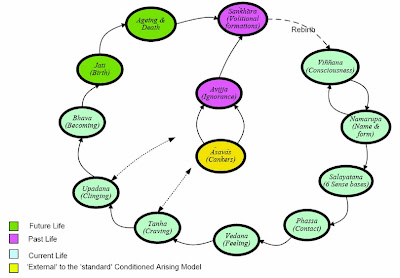

One of the three unthinkable subjects in Buddhism (an assertion that Bhante Dhammawansha has repeatedly told in his Dharma talks that I have attended) relates to the immutable notion of Cause and Effect. Variously known as the Principle (some have used the more forceful term, Doctrine) of Causality, Conditioned Arising, Dependent Origination, Dependent Co-Arising, and the related widely popular Karma, the original Sanskrit term that has been absorbed into the English lexicon, which is simply translated as Action, the notion encompasses the ramifications implied in many of our common sayings such as “you reap what you sow,” “crime does not pay,” and much more since its payback, in the present-day parlance, is not restricted to the present life, but over the so-called Three Life Interpretation (see Figure below).

One of the three unthinkable subjects in Buddhism (an assertion that Bhante Dhammawansha has repeatedly told in his Dharma talks that I have attended) relates to the immutable notion of Cause and Effect. Variously known as the Principle (some have used the more forceful term, Doctrine) of Causality, Conditioned Arising, Dependent Origination, Dependent Co-Arising, and the related widely popular Karma, the original Sanskrit term that has been absorbed into the English lexicon, which is simply translated as Action, the notion encompasses the ramifications implied in many of our common sayings such as “you reap what you sow,” “crime does not pay,” and much more since its payback, in the present-day parlance, is not restricted to the present life, but over the so-called Three Life Interpretation (see Figure below).A concomitant belief is Rebirth, which I personally prefer over another oft-used term, Reincarnation. Both beliefs predate Buddhism but have become two of the central tenets in Buddhism and are inseparable in the sense that denying one makes it that much harder to accept the other. Both constitute a huge mental block for lay believers as empirical evidence of their manifestation in our daily life within the lifespan as we know it is indeed far and between. Living counter proofs abound: rampant poverty and other social scourges, the bad guys got off scot-free while the good guys, victimized. Even those who have taken the Three Refuges may still harbor reservations as amply blogged here.

This apparent incongruence that may seem to require a leap of faith, a rather stupendous one at that, to bridge was explored in the 12th Dharma Session of the Middle Way Buddhist Association held yesterday (Jan 19, 2008) at its Pinellas Park venue, led by Bhante Dhammawansha.

As usual, the session started with sitting meditation, each attendee electing to sit cross-legged on a cushion or on a chair in accordance with personal preferences and perhaps the dictates of physical condition peculiar to each. I assumed my position on a chair and tried to lose myself in mental liberation from random thoughts.

Even though I have several such feats under my belt accumulated since day one (March, 2007) of the formation of MWBA, my mind was still drifting in and out of brief clarity (the tick-tocking of the wall clock was all I heard, and actually counted), and what seemed like an eternity of muddled state where different sounds/noises vied for my attention, from which I was awakened, thanks to gravity, by my body sensing an imminent forward lurching motion (or was it all in the mind?), a warning that the mind was heading toward stupor thus losing control over the body. Anway, I was relieved when Bhante's calm voice came into my consciousness, signifying the end of yet another tussle in the on-going saga of my journey on the path of meditation.

Bhante started the Dharma talk by observing that we don't like to take responsibility. We deem gifts from others as ours, even borrowed ones. But once they are broken, they are no longer ours. This refusal to take responsibility runs counter to the very fabric of causality that every action begets a reaction as embodied in the law of physics governing Nature, and has consequences in human interaction.

However, these consequences will only manifest when the conditions are conducive, or ripe. For example, our presence here in the morning was the convergence of many conditions: Tom organized, the venue was available, Bhante was committed to lead, and the attendees were informed and made the trip through the foggy weather. Thus, Buddhism denies that an action is the result of one condition alone being fulfilled. A simple illustration to understand the concept of dependent origination is the system of English alphabets where B comes after A, C comes after B and so on. If there is no B, then there is no A, and so on.

The Buddha rejected three reasons offered to explain why something happened:

a) previous karma;

b) external agencies/controller;

c) no reason.

In the Buddha's teaching, the Noble 8-Fold Paths, a mainstay of the Middle Way, serve to exemplify the working of the cause and effect:

First we must have the right view/understanding. Then we will have the right thought, the right speech, the right action, the right livelihood, the eight effort, the right mindfulness, and the right concentration in that order. To bring out the human wisdom, we need to search, experiment, and investigate, step by step. It's like reaching for the light from the dark, slowly seeing the light for ourselves as we journey as per the admonishment from the Buddha for self verification, i.e., do not believe because He said it, because of fear, and because of scriptures. Indeed, this rejection of blind faith has continued to be echoed by such scientific luminaries as Sir Issac Newton, “In the fight between truth and untruth, truth always prevails,” and Sir Julian Huxley, a 20th century English biologist and humanist, “No reason to believe anything without experimentation.”

Bhante then went ahead to put in words the causal relationships (the twelve links) that lead to our suffering, starting from our body to the ultimate source: ignorance. Rather than transcribing verbatim what Bhante had explained, I found a graphical representation here that could perhaps illustrate the linkages in the same way, but entailing the three life interpretation as an amplification. Thus, it is said that ignorance is the greatest rust, while wisdom is the greatest gem.

Conditioned Arising - The Standard Model as applied to the Second Ennobling Truth (Fig. 1 taken from here. There is also a disclaimer in the source that "the above diagram is not a strictly accurate depiction of the 3 lives view." Click on the figure for an enlarged view.

Conditioned Arising - The Standard Model as applied to the Second Ennobling Truth (Fig. 1 taken from here. There is also a disclaimer in the source that "the above diagram is not a strictly accurate depiction of the 3 lives view." Click on the figure for an enlarged view.A notable feature of the above figure is the cyclical process. Thus, life in Buddhism is viewed as an endless cycle of birth and rebirth with no beginning and no end, the wheel of samsara. And the ultimate liberation lies in getting out of the samsara through enlightenment. We can experience such a cycle in our daily life as well, a prime example of which is the hydrological cycle that traces out the path of water, for example, in the mighty Mississippi River.

In karmic terms, some may view the 2004 South Asian tsunami catastrophe as a contradiction. Then there are quarters who attributed the carnage to the absence of faith in God. However, in the worldview of Buddhism, the event is a natural phenomenon spawned by an imbalance in the four elements that constitute the world: water, fire, earth, and air.

The confusion arises from our inability to separate culture and religion, often seeing the world through lenses that are colored by our prejudices and obfuscated by layers of ignorance. Therefore, the Buddha exhorted us to go deeper to understand reality and as such, He had devised many ways to help put ourselves on the path to enlightenment, as befitting his exemplary role as a great physician for mental diseases.

In the interaction that followed during the vegetarian lunch, I was given an idea for my next reading project in trying to better understand how Buddhism that professes no self would be able to reconcile with the notion of individuality that is so deeply ingrained in the western ethos: Buddhism without Beliefs by Stephen Batchelor. Thanks, Olivier.

No comments:

Post a Comment